A sigmatropic reaction in organic chemistry is a pericyclic reaction wherein the net result is one σ-bond is changed to another σ-bond in an uncatalyzed intramolecularprocess.[1] The name sigmatropic is the result of a compounding of the long-established sigma designation from single carbon–carbon bonds and the Greek word tropos, meaning turn. In this type of rearrangement reaction, a substituent moves from one part of a π-bonded system to another part in an intramolecular reaction with simultaneous rearrangement of the π system. True sigmatropic reactions are usually uncatalyzed, although Lewis acid catalysis is possible. Sigmatropic reactions often have transition-metal catalysts that form intermediates in analogous reactions. The most well-known of the sigmatropic rearrangements are the [3,3] Cope rearrangement, Claisen rearrangement,Carroll rearrangement and the Fischer indole synthesis.

3,3-sigmatropic reaarangment after that decarboxylation

The mecahnism involves the abstraction of proton from the active methylene group of the keto-ester followed by intramolecular Michael addition and decarboxylation to yield the unsaturated ketone compound

Firstly the ketoester tautomerize to give a enol ester and then a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement occur (or simply called Claisen Rearrangement). After that, the substrate become a keto-acid and it undergoes decarboxylation under heat.

3,3-sigmatropic reaarangment after that decarboxylation

The mecahnism involves the abstraction of proton from the active methylene group of the keto-ester followed by intramolecular Michael addition and decarboxylation to yield the unsaturated ketone compound

Firstly the ketoester tautomerize to give a enol ester and then a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement occur (or simply called Claisen Rearrangement). After that, the substrate become a keto-acid and it undergoes decarboxylation under heat.

Claisen rearrangement

Main article: Claisen rearrangement

Discovered in 1912 by Rainer Ludwig Claisen, the Claisen rearrangement is the first recorded example of a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement.[10][11][12] This rearrangement is a useful carbon-carbon bond-forming reaction. An example of Claisen rearrangement is the [3,3] rearrangement of an allyl vinyl ether, which upon heating yields a γ,δ-unsaturated carbonyl. The formation of a carbonyl group makes this reaction, unlike other sigmatropic rearrangements, inherently irreversible.

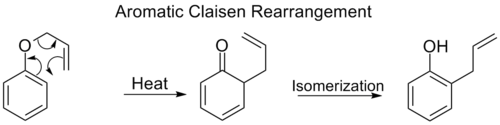

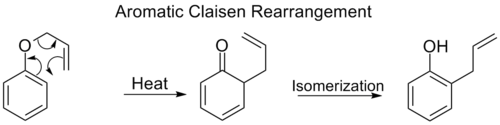

Aromatic Claisen rearrangement

The ortho-Claisen rearrangement involves the [3,3] shift of an allyl phenyl ether to an intermediate which quickly tautomerizes to an ortho-substituted phenol.

When both the ortho positions on the benzene ring are blocked, a second ortho-Claisen rearrangement will occur. This para-Claisen rearrangement ends with the tautomerization to a tri-substituted phenol.

Cope rearrangement

Main article: Cope rearrangement

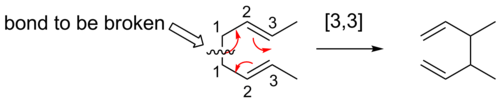

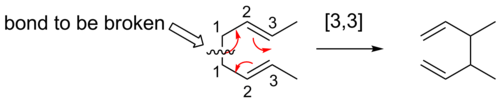

The Cope rearrangement is an extensively studied organic reaction involving the [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-dienes.[13][14][15] It was developed by Arthur C. Cope. For example 3,4-dimethyl-1,5-hexadiene heated to 300 °C yields 2,6-octadiene.

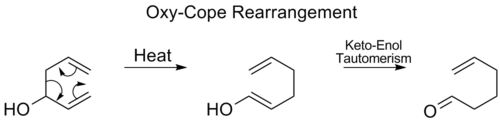

Oxy-Cope rearrangement

In the Oxy-Cope rearrangement, a hydroxyl group is added at C3 forming an enal or enone after Keto-enol tautomerism of the intermediate enol:[16]

References

- ^ Carey, F.A. and R.J. Sundberg. Advanced Organic Chemistry Part A ISBN 0-306-41198-9

- ^ a b Woodward, R.B.; Hoffmann, R. The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry. Verlag Chemie Academic Press. 2004. ISBN 0-89573-109-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miller, Bernard. Advanced Organic Chemistry. 2nd Ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. 2004. ISBN 0-13-065588-0

- ^ Kiefer, E.F.; Tana, C.H. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1969, 91, 4478. doi:10.1021/ja01044a027

- ^ Fields, D.J.; Jones, D.W.; Kneen, G. Chem. Comm 1976. 873 – 874. doi:10.1039/C39760000873

- ^ Miller, L.L.; Greisinger, R.; Boyer, R.F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969. 91. 1578. doi:10.1021/ja01034a076

- ^ Schiess, P.; Dinkel, R. Tetrahedron Lett., 1975, 16, 29, 2503. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(75)80050-5

- ^ Carey, Francis A; Sundberg, Richard J (2000). Advanced Organic Chemistry. Part A: Structure and Mechanisms (4th ed.). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. p. 625. ISBN 0-306-46242-7.

- ^ Klaerner, F.G. Agnew. Chem. Intl. Ed. Eng., 1972, 11, 832.doi:10.1002/anie.197208321

- ^ Claisen, L.; Ber. 1912, 45, 3157. doi:10.1002/cber.19120450348

- ^ Claisen, L.; Tietze, E.; Ber. 1925, 58, 275. doi:10.1002/cber.19250580207

- ^ Claisen, L.; Tietze, E.; Ber. 1926, 59, 2344. doi:10.1002/cber.19260590927

- ^ Cope, A. C.; et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 441. doi:10.1021/ja01859a055

- ^ Hoffmann, R.; Stohrer, W. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 25, 6941–6948. doi:10.1021/ja00754a042

- ^ Dupuis, M.; Murray, C.; Davidson, E. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 26, 9756–9759. doi:10.1021/ja00026a007

- ^ Berson, Jerome A.; Jones, Maitland. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 22, 5019–5020. doi:10.1021/ja01076a067

- ^ Carrol, M. F. J. Chem. Soc. 1940, 704–706. doi:10.1039/JR9400000704.

- ^ Fischer, E.; Jourdan, F. Ber. 1883, 16, 2241.doi:10.1002/cber.188301602141

- ^ Fischer, E.; Hess, O. Ber. 1884, 17, 559. doi:10.1002/cber.188401701155

- ^ van Orden, R. B.; Lindwell, H. G. Chem. Rev. 1942, 30, 69–96. doi:10.1021/cr60095a004

- ^ Robinson, B. Chem. Rev. 1963, 63, 373–401. doi:10.1021/cr60224a003

- ^ Robinson, B. Chem. Rev. 1969, 69, 227–250. doi:10.1021/cr60262a003

- ^ Jensen, F. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1989, 111, 13, 4643 – 4647. doi:10.1021/ja00195a018

- ^ Klarner, F.G. Topics in Stereochemistry, 1984, 15, 1–42. ISSN 0082-500X

- ^ Kless, A.; Nendel, M.; Wilsey, S.; Houk, K. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1999, 121, 4524. doi:10.1021/ja9840192

No comments:

Post a Comment